The Law of Unintended Consequences is not new. People have noticed it for a very long time, even before the law had a name. The idea comes from simple human experience. People do something with a good plan, but something else happens that they did not expect. Sometimes that surprise is helpful. Many times, it causes new problems. The law reminds people that every action may lead to results they do not plan.

Understanding the Law of Unintended Consequences

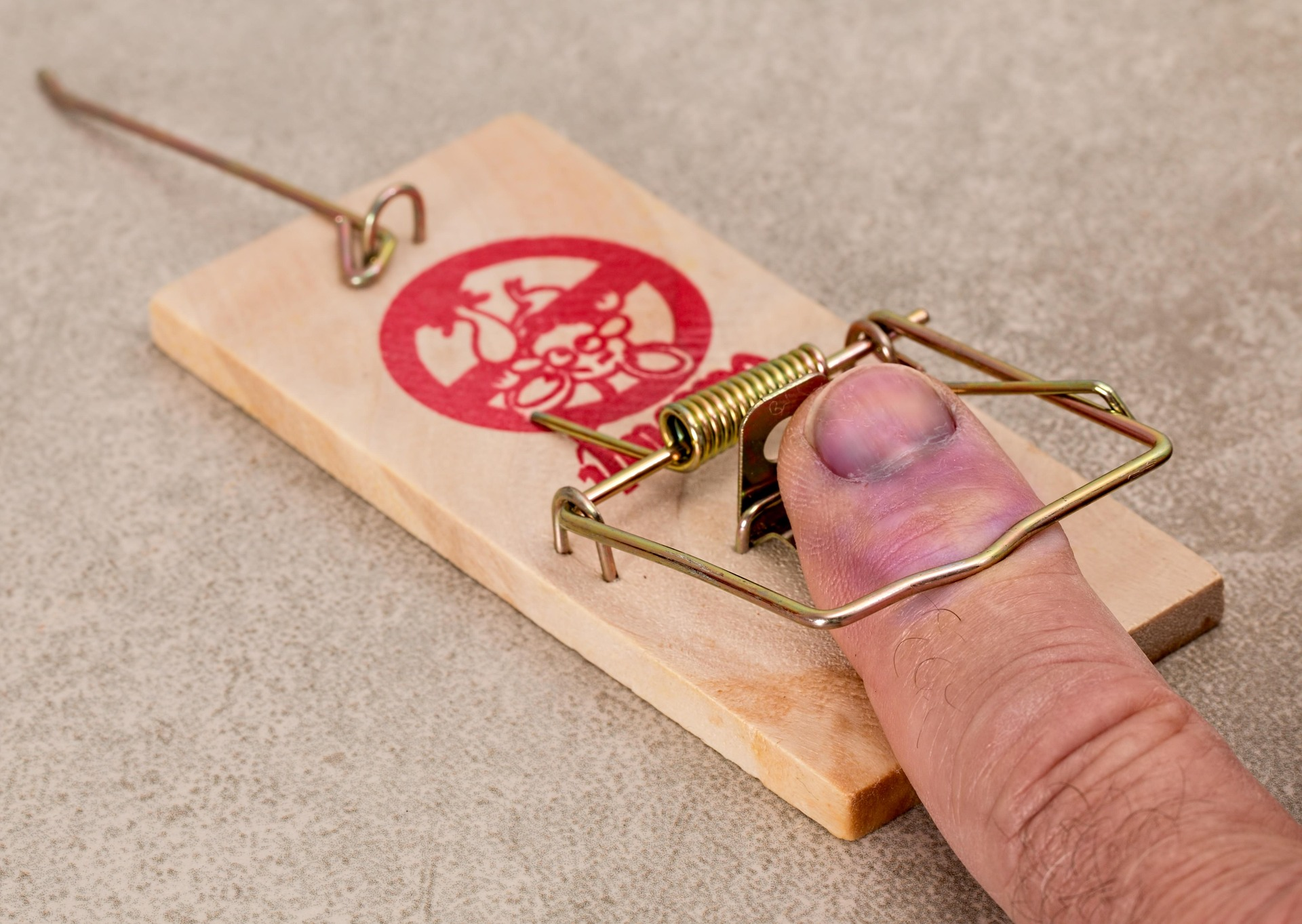

The Law of Unintended Consequences explains what happens when people do something with good intentions, but the result is not what they expected. It shows that even careful plans can create problems.

These problems may not appear at first. Later, they may cause harm or change things in ways no one wanted.

This law is important when working on sustainability programs and out in the real world. When introduced in academic theory, results are consequential to the theorists, but not overwhelmingly felt in the “real world”. In terms of the practical application of academic (or any) theories, real lives are at stake. Moreover, those lives are the most vulnerable among us.

People want to help others. These are the people who are most in need of help. Their meager lives have precious little room for unintended consequences. Their precarious situation is already quite bad enough. Unintended consequences do not help. They may even hurt the very people or natural environments they were “intended” to protect and serve.

Early Thinking on the Idea of Unintended Consequences

A well-known thinker named Adam Smith wrote about ideas conversely related to unintended consequences in the 1700s. He explained how people acting for their own good may help society in ways they never planned.

His idea was about good surprises. But later thinkers started to look more at the harmful surprises. These thinkers saw that even helpful actions could lead to problems if people did not think carefully.

The Wording of the Law

The phrase “Law of Unintended Consequences” became popular in the early 1900s. An American sociologist named Robert K. Merton wrote a paper in 1936. He studied how actions in society often led to effects that nobody expected.

He called these effects “unanticipated consequences.” His work helped explain how even smart people and good plans could miss important details.

Merton’s Contribution

Merton explained three main types of unintended consequences.

The first was a positive surprise.

The second was a bad result that came from the action.

The third was when the result made the problem worse.

He showed that these outcomes could come from simple mistakes, a lack of information, or even because of people ignoring facts they do not like. His work helped many others understand why some policies and programs do not work as planned.

Intentions Do Not Determine Outcome

People often say they mean well. They want to fix poverty, stop pollution, or save forests.

Wanting to help is not enough.

The results must be measured. The only way to know if something works is by looking at what really happens. If a program makes life harder for people, then it does not matter if the idea was good. The outcome is what matters.

Any program that fails to help people or protect the environment cannot be seen as successful, even if the planners had the best goals and intentions.

Examples of Unintended Consequences in Action

Sometimes, a rule or program tries to stop one problem but creates another.

A rural improvement program may ensure that everyone who owns their home now has a much safer, more secure, and nicer home. What of the poor person who was barely able to pay their taxes before?

They now have an increased tax bill and increased local costs. The median income has risen, but they run a small, home-based business, supplemented only by their small garden and maybe some chickens and pigs. They now risk homelessness and deprivation because someone felt they needed to live in a better neighborhood. And now they are homeless.

Government policies are not immune from the Law of Unintended Consequences either. California has banned forestation to the extent that even dead brush cannot be legally removed. What should be small and easily contained wildfires now destroy entire portions of some of the largest cities in the world.

How about creating new reefs? Places for all manner of fish to call home, and some kind of foundation for the coral beds to grow. What could possibly go wrong?

The Osborne Reef is a large artificial reef in the ocean near Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In the 1970s, people wanted to build a new home for fish and sea life. They thought they could use old car tires to make this happen. So, workers placed more than two million tires into the water. They tied the tires together with metal and plastic straps.

At first, people believed the tires would stay in place and help sea life grow. But over time, the straps broke. The tires started to move around. Many of them damaged the natural reef nearby. The tires did not help sea life. Instead, they created a big problem.

Why The Local Context Is Important for Mitigating Unintended Consequences

When people from outside a community make decisions, they often do not have even the most basic understanding of the local context. They may use ideas from books or from other locations. These ideas may not fit the place they are used in.

If people do not ask local communities what they need, they risk failure. Local people know what works. They also know what causes problems. Programs that do not include local voices often fail. That failure can bring more harm than good.

Success Metrics Must Be Based on Results not Intention

Good plans must include ways to check the results. People must look at what really changes after a program starts.

They must check if the people are healthier, if the land is better, or if poverty is lower. They must also watch for harm. Even small problems can grow bigger over time. If the results are bad, the program must change. It does not matter how good the plan looked on paper.

Only real-world results matter. Feelings are important, but reality remains unimpressed by intentions or the very real unintended consequences resulting for any reason.

The Law of Unintended Consequences shows that people must be careful when starting any new sustainability program. This is especially true for systemic sustainability programs that must focus on the integration of economic, environmental, and social sustainability.

Good intentions are not enough. Results are what matter.

Program developers and designers must listen to local voices, understand the environment, and test all viable new ideas. If not, the result may be worse than the original problem. The only real way to measure success is to look at the final outcomes. Only by doing this can people create lasting and helpful change while mitigating the potential for unintended consequences.